The author of the design of the new Prague landmark Gilles Delalex: Even social housing deserves luxury. It won't be created by expensive paving stones

17/2/2025

You came to Prague to present the book Holy Highway. Are you an impassioned driver?

Not at all. I have a license, but I live in Paris, where you don't have much need to drive. We're not so much interested in the highway as a place for cars, but as a special kind of space.

When did your fascination with transport infrastructure begin?

I remember photographing highway intersections in Montreal when I was a student. My thesis project was also near a highway, then came reading J.G. Ballard (author of Concrete Island, about an architect forever stuck on a highway). Architecture was evolving in its view of infrastructure, and in the 1990s people were talking about mobility, logistics and traffic flows. Today, the discussion is influenced, in a good way, by the ideology of sustainability, which has made transport an uncomfortable topic.

Although we criticise motorways, we still use them because we have no other choice. We still rely on modern infrastructure. It is a habit and, in a way, a heritage. It is the same with buildings. Here on the Dejvice Campus, you walk past massive buildings based on modernist urbanism, which is criticised, yet we live with it. I think the Holy Highway speaks volumes about our relationship with modern traditions and also about how difficult it is to come to terms with them at the moment.

You've photographed objects around motorways that are repeated all over the world. Why is it important for you to capture petrol station logos in hundreds of images? The Shell logo is the same everywhere in Europe, the CEOs of multinational companies want it that way.

Oh yes, the logos. That's how we started our motorway research 20 years ago. We were concerned with standardisation and a critique of how capital is trying to make the world more or less the same everywhere. My point then was to show that things are more different than they look. You used the example of Shell, but you will not find two exactly the same pumps in the world, although Shell would of course like that. But the reality of the world is more complex.

Are buildings in globalised world still affected by local conditions?

Yes, there are a number of conflicting forces. But it can also be said that sometimes the locals themselves are to blame for globalised architecture. Look at the developers who are building office buildings, and it doesn't matter if it's in France or the Czech Republic. These are not big global forces. It's just that the two guys have exactly the same taste for some reason. They want the same building! But even so, they never build exactly the same.

You're comparing gas stations and highways to classic urban districts. You mentioned in one of your lectures that gas stations are the opposite of gentrified neighborhoods. Is that really true?

First we looked at standardization and then we looked at the social aspect. I was interested in why these spaces are so appealing, you often see them in films. I think there's something wild about them and things happen there that couldn't happen anywhere else. Like in train stations it's always weird too, there's always strange people hanging around. And the same thing happens here. The motorways seem to be very controlled, lots of rules about speed, direction of travel. Cameras lurking everywhere, so the environment seems very controlled. But there are no social rules here and nobody even tells you what to do. In fact, the rest areas seemingly belong to no one, and people run, exercise, vomit, have sex and sell illegal stuff. You could hardly do any of that in the centre.

You say yourself we're under camera surveillance.

Yeah, but they usually don't work! And there's always a way around them. There's a lot of illegal stuff going on, that's just the way it is.

Did you ever get into trouble during your research?

Not really, I think these places are pretty safe.

I'm still thinking about gentrification, though. I mean, gas stations are designed to make you spend as much as possible at them. They're trying to get us to buy a bunch of scented junk, and not just gasoline.

Sure, but you still have different kinds. Once you cross state lines, you see the difference. In some countries, gas stations are just little boxes, and you don't spend much time at them. In other places, you're greeted by a huge restaurant. Then you meet the gas stations associated with the surrounding area and find that that's where the locals congregate.

How can your research inspire the everyday work of an architect?

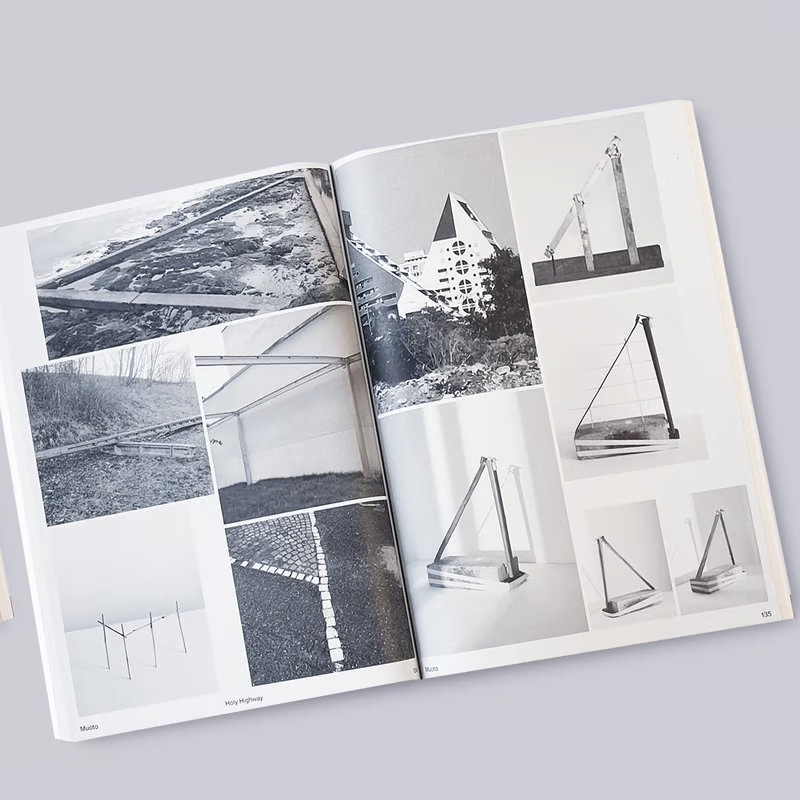

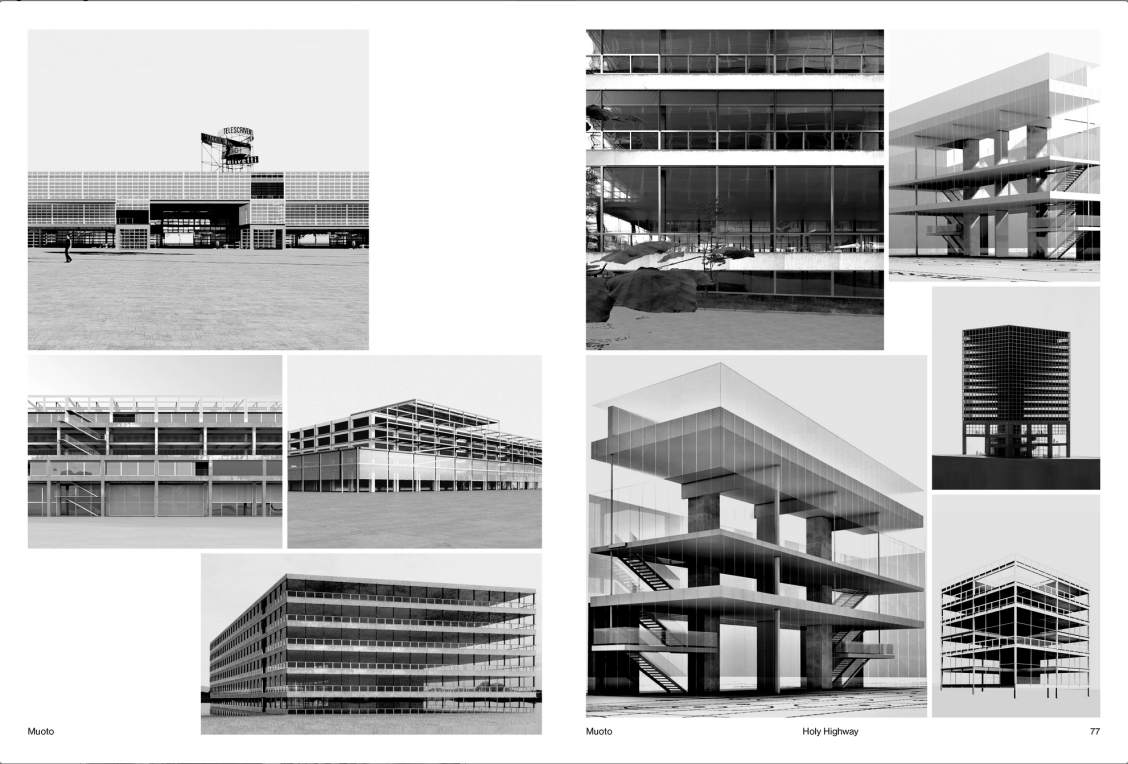

We have created a spectrum of images from which we draw references. In our office, when we start a project, we pin images all over the wall, for example, inspiration about materials. A lot of the photos we use come from the infrastructure world. Often these are technical buildings with platforms, balconies, strange staircases, and antennas. This whole technical vocabulary can be quite poetic. But it doesn't mean that we are trying to copy the world of infrastructure. Sometimes we discover an object and say to ourselves: Wow, that's strange. What's the story? How did it get here in the first place? And then it finds its way and imprints itself on one of our projects.

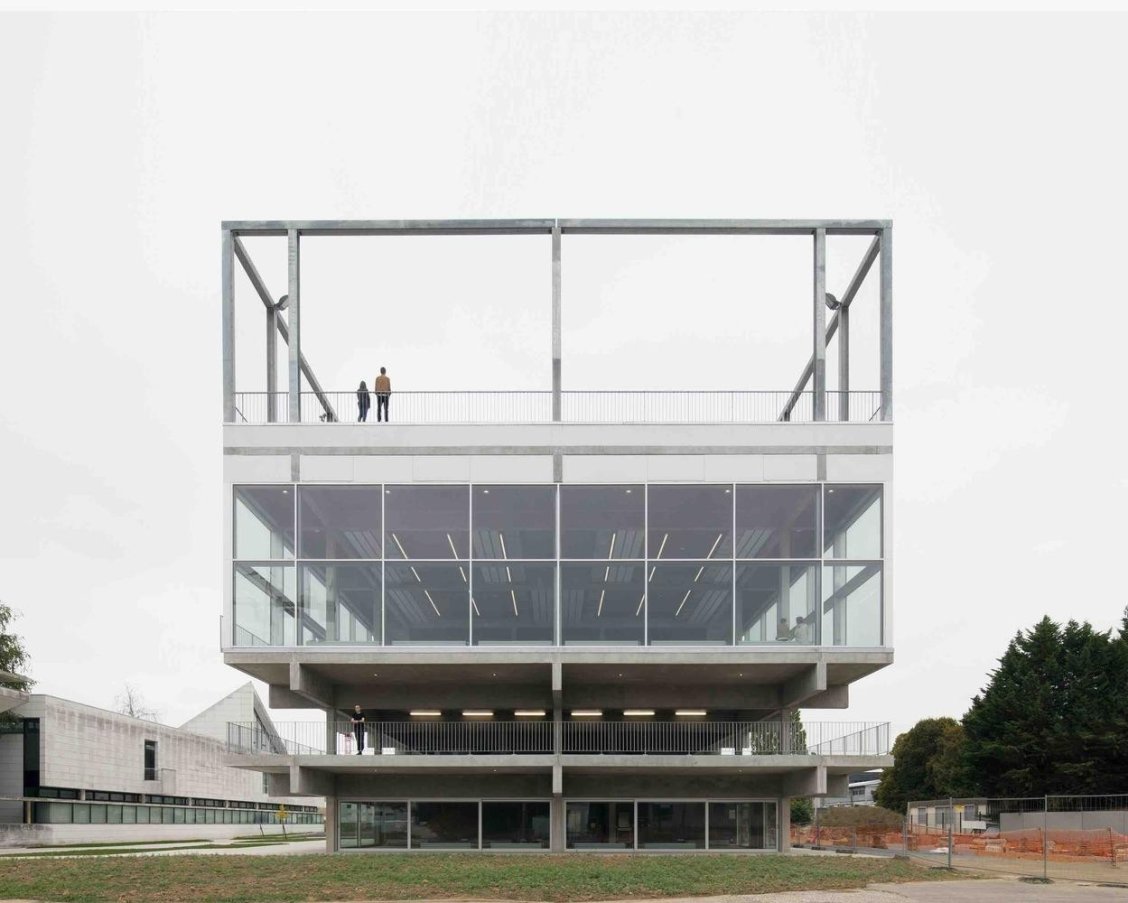

When you were building a student house on the new Paris-Saclay campus, it must have felt almost like a motorway. There were only a few haphazardly placed university buildings, resembling logistics centres, and a car park.

Initially, our infrastructure research was more academic and not connected to the buildings we were designing. But then we had to design several buildings in places with almost no context. There were parking lots everywhere, a few roads, and sometimes fields. The student house is quite small, it's some 2,000 square metres of space, it has a restaurant, a café, exercise rooms and two basketball courts on the roof. An open staircase connects the floors. It should serve as a meeting point for everyone on campus.

You value yourself on the authenticity of your materials, you try to use them sparingly. But that must be problematic these days, houses are becoming complex technical machines. The pressure for ever thicker insulation also forces architects to use complicated sandwich solutions.

I don't think we could build this house to today's standards. And we submitted the study in 2012. But even then we had to find a lot of unconventional solutions. We hid the insulation in different ways and we came up against conflicting rules. Even for fire escape routes. Our staircase is in the middle of the building, but we considered it to be outside because it gets rain anyway. Eventually we did, but often the process was absurd.

Why do you often build houses on cantilevers and columns? The winning design for Prague's Revoluční Street barely touches the ground.

We like to hang things in the air. No, I'm kidding. I think the situation in Revoluční was completely different from the Paris campus and pushed us into a modern layout. The neighborhood is very strong, there's a lot of things going on, so we didn't want to be too talkative.

How the project evolved. Did you also consider the option of a classic corner house?

We tried everything, but we said we couldn't succeed in a competition with a classic layout. How will one design differ from the other? We thought we'd do the best we could, turn the balconies towards the river and give the residents a view.

How did you get together with your Czech colleagues from Peer Studio?

They called us. You'll have to ask them why they chose us. For us, it was actually the first round of the competition. But it's been a very fruitful collaboration so far.

Why did you decide to clad the staircase towers in a distinctive stone?

It's to distinguish the two parts of the building from each other. And stone can do that. We want the suspended part to be as modern and light as possible. So we had to find a different expression for the towers, and we thought about marble because of the historical context. But I want to say that this is only a competition proposal for now, we will still be specifying how to give the towers the expression ‘honest masonry’, while the other part will be a light metal structure.

You mention a strong historical context and a lot of valuable houses around, but the waterfront is in a very dismal state, in fact it's also a highway full of cars.

Hopefully the project will change the neighborhood, we can't affect it directly but a lot of things should improve. Maybe that's why the blank facade has stayed for so long, because the whole place is neglected. It is an important point for Prague, visible from afar. It has a strong symbolic value, which is why we think it is appropriate to place a very specific building here.

You create a lot of public space on the site. But isn't our problem, perhaps even in the Revoluční area, that we already have a number of public spaces that are poorly maintained?

The measure is not the quantity, it is the attention paid to the public space. As an architect you can draw attention to it. Here you have a baroque house, a gable wall of newer houses, and there's no room to build anything else in between. So the space will always be there and it needs to be given meaning and value. We said that if we put the house on top of it and create a passageway, there's a decent chance that it will become a successful public space. It is quite intimate, I agree that a large public space is not a good thing either. Nice town squares aren't the greatest.

Completely different topic. Why did you put a giant disco ball in the French pavilion at the Venice Biennale?

We wanted our architecture to invite action. We said to ourselves: Let's make a theatre. We wondered if the whole pavilion would be a hall, but in the end we made it inside a round building. We asked artists and researchers to fill it with programs. The disco ball was a metaphor for the theme of the party, but you could easily say it was a planet or a balloon.

In Venice today, everyone is trying to deal with the crises and problems of the contemporary world. And then suddenly there's a disco ball.

It was a place for debate. A crisis is a specific moment when you move from one epoch to another. And the change is uncertain, because you still have the rules of the old times, at the same time new ones are being created, and you don't know what's coming.

But in times of crisis, is there any time to party and disco?

No, we have to think about the longer term. When we said ‘party’, it was a metaphor, of course. We were preparing for a big feast, a big thing together. Not the party, but the part before. I think there is a recurring theme in the debate about solutions to the crisis today: It's urgent. We must act now. We don't have time to think. On the contrary, you have to think twice as much. It is time to prepare and bring people to the debate table.

Crises are always very interesting moments in history. There is a clash between those who say that the past was better and we have had a good time. And they are confronted by people who say that we have no choice but to imagine something new. Crises have happened many times in history. But each time we seem to forget that there has been another crisis before. I think that Western society feels the arrival of another world, of China, India and other powers. We feel that the whole legacy of the Enlightenment is collapsing. And we wonder what we have done to cause it.

The decay of western society parodying your Parisian apartment building 23 dwellings. Each of the owners could choose their facade?

Yes, I think we're exploring different moments of decadence. It's not exactly decadence, people are just saying over and over again: things are going to go wrong. And it does happen. In the case of both the Biennale and the 23 dwellings in Paris, we are pointing to the problems of coexistence. We have a problem with the creation of collective values, which is written into housing construction.

Weren't you afraid that people would think collectively and choose only one facade?

That could happen, it would be a disaster. (Laughter)

You compared the house to unfinished buildings in, say, South America or Africa, where the skeleton is occupied by poor families and gradually filled in. Doesn't the inspiration from shantytowns alone signify the crisis of the West?

Perhaps, it was mainly a message about collective housing. The term itself already sounds a bit of a downer, because individual housing is better. We wanted to show that collective housing can have a number of qualities - rooftop access, open staircases and large common areas, local public amenities and shops. In fact, the luxuries you can get with flatted development are easily accessible. It's not the paving and the surface of the facade that creates comfort.

You have also built social housing, for example on Rue Stendhal near the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris. The apartments look luxurious. Is it difficult to promote housing with these qualities for the socially disadvantaged?

The investor was the city of Paris, which considers social housing to be a major issue. It's actually two buildings and each is designed for different types of social housing. One is really for people who have been hanging around on the streets. But we said that there was no point in treating them differently. It was difficult to build, it took eight years. The neighbours weren't too keen on it. I think we tried to provide social housing in the most dignified way.

Politicians in the Czech Republic also talk about social housing, but I'm not sure they would be afraid to build something that looks so posh. After all, a bathroom with a giant window and a view of the city is for the chosen few.

And yet it's not hard to achieve that quality. (laughs) Big balconies, big windows, just modern comfort. When we entered the competition, we said to ourselves: It's so easy, we have a south orientation, so let's design big balconies there. Why have we long forgotten these simple procedures?

The interview was conducted by Pavel Fuchs.