Interview with Professor Petr Hájek. About the concert hall in Císařské Lázně and what is a toothpick, a brick and a paper clip for?

16/12/2024

Your hall in the Imperial Baths is bathed in the waves of the glory of three architectural awards: the Czech Architecture Award of the Czech Chamber of Architects, the Grand Prix of Architects of the Architects' Association, and the Building of the Year of the ABF Architecture Foundation. Our readers may be familiar with the multifunctional hall but might be interested in your approach to the commission. Especially since we are in the space of a National Historic Landmark.

When we began the commission, the brief was for a spa-like hall with a large auditorium for about six hundred spectators – hence the balconies around the perimeter of the hall, a series of escape exits, etc. Not to mention a multi-storey air-conditioning system underground. That is why complex debates with the monuments' authorities have been going on for many years without success...

Architecture is sometimes compared to cooking. Nothing original, but I'll use the analogy here. What we want in the pot is what we all start with. We started with that too, when we were looking for a response to the brief there. However, we decided to turn our first question inside out: what will fit in the pot. First, we showed what ingredients, and more importantly in what proportions, can be baked to make a good cake. We demanded compromises from the actors. The reduction was painful... But then we got there pretty quickly.

Incidentally, when Neutra built his magnificent homes in California, he used large spans of steel – unprecedented in residences until then: stunning roofs, flying slabs over living spaces with views of the horizon... Architects usually start with a concept and then the construction company comes in. Neutra turned it around. He designed and built from what was on sale in quotes. After leaving F. L. Wright's office, he moonlighted in various ways and, to put it lightly, took a part-time job at the local Ferona. That way he knew which steel elements were the cheapest. And those were the ones nobody used, the biggest and longest. And suddenly the roof was not eight metres wide, but fifteen... And a beautiful four-metre cantilever to go with it. So there was a flying living space with no supports. And that's the joke of the whole thing. You make full use of what's in the pantry.

So...

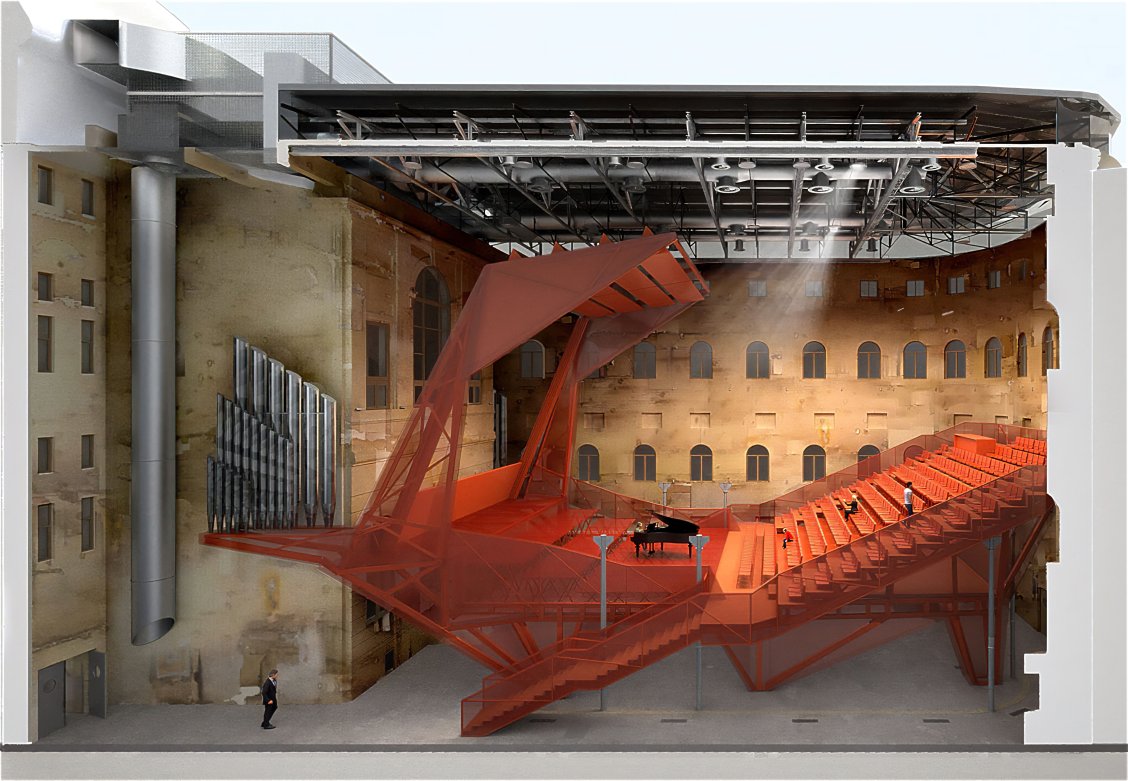

...So we've saved similarly, and instead of ten supports, we've got six, and an amazing extra room under the belly of the auditorium to go with it. Through a reduction in the original brief, we have proposed a use to the conservation officer that will go with the grain of the building, so to speak, and not interfere with it structurally. The investor and the management of the symphony orchestra eventually agreed to this. It was a realistic assessment of what was possible in the possible.

You stress the goal. For the sake of clarity of your strategy, let me stick to the original programme for the reconstruction of the baths.

The initial objective was clear: to save the building from collapsing. When the money was found for the repairs and the reconstruction project was drawn up, it was only later, somewhat illogically, that the question of the programme came up. Above all, for technical and economic reasons, the baths were out of the question on a historic scale. At the first meeting of the colloquium, the option of something like a market hall or an arcade similar in concept to Prague's Black Rose, i.e. a multifunctional rental building with shops and offices, was on the table.

It didn't seem appropriate or dignified at the time. Moreover, the Karlovy Vary Symphony Orchestra had no place to play and no headquarters. This place, this building, was an ideal opportunity. Ironically, there was a memorandum for the construction of a hall, but this document could not be fulfilled because there was no solution that was acceptable to everyone.

By the way, the whole new idea was initiated by Petr Kropp, a prominent Dutch architect of Czech origin, who was the chief architect of the city at that time - he initiated it together with Petr Polívka, the former director of the Karlovy Vary Symphony Orchestra. There are plenty of historical buildings that have been repaired, but the Imperial Baths are extraordinary, so they both had the ambition to add a hall of extraordinary parameters.

We were known to have completed a multifunctional hall in DOX+, in Litomyšl in the Riding Hall on Castle Hill and in the Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc.These interventions took place in different types of spaces with significant operational and spatial constraints.And this is probably what made the difference for us.Our verification study then confirmed that the music hall could indeed fit into the hall with the compromises mentioned. The acoustician Martin Vondrášek, who worked with us on all of these halls, and Petr Vlček, the director of the acoustic company AVT Group, who worked on the last two projects (DOX+ and Císařské lázně - ed.), had a great deal to do with the result.

The goal you mentioned brings us to the key to the project, i.e. the brief. In one of your earlier interviews on Archiweb, where you talked about your Laboratory of Experimental Architecture, you stressed the importance of critical analysis of the brief. It is this approach that seems to open up space for finding compromises. Could you elaborate on it more specifically?

Compromise can be made when negotiations are stalled and there is a risk that nothing will happen. I will give the example of air conditioning. The standard for assembly areas required up to about 40 times the air change for the entire time the hall was in operation, and effect means a gigantic machine room. But in a concert hall, you have a break and you can change the air quickly during the break - at high speeds and high noise levels. Which was our option. So no double-decker engine room, but no single-decker engine room either. Just a compact container on the roof, which is also there today, and which you don't even notice.

In the author's report, you describe the hall as a "tool" that works traditionally but also allows for experimentation. The Czech Philharmonic Orchestra performed here, but there was also a popular music concert where the stage was retracted and a cauldron was created under the stage. How would you sum up the features of your instrument?

You can acoustically tune our hall to the necessary parameters of a particular production, just like a musician tunes an instrument. In the end, it can be considered a musical instrument - in terms of reflections and sound propagation within the enclosed space that resonates. The turf machine has been replaced by a musical machine. Or machine for the machine.

Memory

You also call the hall the Red Crab. Before we get to the functioning of the crab in the hall, what is your relationship to the neo-Renaissance baths by Fellner and Helmer?

The inspiration for the hall was an old drawing of a robotic crab from my childhood ABC magazine. I think the nickname was first used by Petr Vlček. If you ask me - the building is as impressive to me as the whole 19th century is to me. Its legacy is still relevant and modern from today's perspective. It's just that the language of architecture is different today and then. The principles remain, and that's why I didn't feel that we were designing something contrary to the existing building.

By the way, if you had the chance, would you do anything differently today?

My only regret is that I was not able to dissuade the investor and the conservationist from plastering and painting the historic space. The hall used to be a machine shop with cast-iron scaffolding and an elevator. Peat-filled tubs came out of the peat pavilion through an underground passageway to enter the bathrooms. The fumes and construction interventions created beautiful paintings on the walls like paintings by Boudník. Now they're gone. The essence has been lost. A relic and a testament to the times.

What were the reasons?

In the hall, a series of installations, from the electrical system to the roof drains, were cutting into the perimeter wall. I wouldn't mind even if they were admitted on the surface. On the contrary. I wouldn't mind new window treatment marks, etc. But the prevailing opinion was that it would make it look unfinished. Complete nonsense. It always was. I don't understand why these values are not protected. I think it's a debt to conservation, which in my experience prefers such solutions. We have a problem with that on all buildings.

Let's go back to the language of the 19th century.

That was the time when things were created that are still in use today: the thermos, the gramophone, the telephone... It was a pioneering time when different disciplines intermingled and inspired each other. The Wright brothers started out with a bicycle shop before creating the first glider at the turn of the century and eventually the airplane. Wings were said to be covered by tailors who covered women's crinolines with fine linen... These are the contexts of the time. The novels of Jules Verne, which predicted the future far ahead, the aesthetics of steamboats... In short, new times, new energy, new ideas.

It's time for the Red Crab. So: how did you come up with the crab?

The basic strategy of life is adaptation. That's why he's so successful. Isn't that a beautiful metaphor? An animal that has adapted here... Maybe if you put a real crab in the space, of the appropriate size of course, it would probably tuck its claws into a niche next to the staircase - and rotate to fit comfortably in the space.

Okay, but why a crab?

I work with inspiration in my designs. They precede the design, but I don't choose them randomly. They're based not only on visuals but on principles. In this case, the inspiration was the robotic crab from the aforementioned old illustration in the ABC Magazine for Young Engineers and Naturalists. I'll remind you that at that time, comics weren't allowed here...

Our hall took on the logic of how it was constructed, and to some extent it also took on its visuality. And meaning. What interested me was the complexity, versatility and adaptation of the robot concept - and I translated that into the design. It doesn't really matter if the inspiration in this case is a drawing from a children's comic book, or NASA's experimental robots for exploring other planets. By the way, these also resemble crabs. They move on six legs and have claws with various tools.

Emotions

What else? What followed the rediscovery of the crab picture?

The world around us is mediated by our senses and we perceive it mainly through feelings. It may surprise you, but even though the design outcome is purely rational, I look for images and feelings first. Then I find the inspiration that corresponds to it, and through it the design materializes or, let's say, legitimizes. What precedes the proposal is intuitive and immeasurable... And therefore, in our society, extremely suspicious (laughs).

It's as if you were fishing in the current of a submerged river... But besides the robotic construction, there is also the theme of colour. The red colour of the hall is very striking. It's not often that such colour is a subject of controversy in architecture, especially when it's a space for music.

For me, architecture is first and foremost a theme of emotion. Red is in the hall for two main reasons. It stimulates the senses. That's the first reason. Whether you like it or not, I read that in your brain and body, this colour triggers a number of biochemical processes - bioelectrical and physiological processes. Your sensitivity is heightened. You hear and see better because your body becomes more alert and its intensity of perception changes. It warms up.

The second reason is scenographic. When you light a scene, the stage stands out. And the parts that are not lit disappear into the gloom. To the human eye, which moves in the gloom and darkness, the colour red shows less contrast than the colour black shows - that is, against its background. I recalled a documentary about hunters who dressed in red for the very same reason.

This effect was evident, for example, during a symphony orchestra concert when the entire stage was lit - when compared to a Bella Adam concert when only the performers on stage were spot-lit.

The question that probably comes to everyone's mind now is, why aren't all concert halls proposed to be red?

Some are being made that way too. One example: the beautiful red hall by LMN Architects in the Voxman Music Building in Iowa, USA. Architects commonly count on the effect of colour. But the truth is that it's not common to see red in music hall interiors on a large scale.

Shouldn't the nature of the music being played also matter? Perhaps it should aim to harmonise the environment, or certainly not to disturb, for example, a certain soothingness of sounds or calmness.

Anyway, that's why the hall offers many possibilities for working with the scenery. You can simply turn off the red; or you can suppress it with appropriate lighting. You can vary the hue and intensity of the colours with the light, and create a soft hug around the hall with the curtain.

Speaking of red... Could you describe its hue?

It's a secret recipe. Something like YK Blue or PH Red (laughs). But it's no secret that besides the colour, there's also a material quantity that plays an important role, I've already mentioned it somewhere: the sound conductivity of the metal of our transformer construction. It can amplify the energy of the orchestra.

Finally, the relationship between music and architecture... It's mysterious. Perhaps omnipotent. This omnipotence can be almost mesmerizing at times, for example through the scenography on the opera stage. Architecture is petrified music..., Goethe said.

It's a beautiful simile. Architecture for me is a notation, something like a musical score of one's own composition. In principle, every structure can also be read as notation... And it can also be set to music. Architecture too. And theoretically, every architecture can be used as a musical instrument. They're hollow spaces encased in a shell that can resonate...

The Turn - School

You are a long-time teacher at the Faculty of Architecture of the Czech Technical University. How do you choose topics for the school studio?

The choice of topics is not as free as it might seem. Architecture is a bounded profession and this is the nature of teaching in the studio. Students have to go through different typologies that are pre-determined. So the basic scope of what everyone should know after graduating from the studio is also given. The only room for difference is what you add on top of that. In my case, the method and the specific assignment.

What do you mean?

My colleague Jaroslav Hulín and I teach a conceptual approach to architecture that works with creative intelligence in the sense that Paul Guilford, the famous American psychologist, describes it in his Joy Test. For example, you had to come up with as many ways as possible, as quickly as possible, to use: a toothpick, a brick and a paper clip. It's the same with architectural tasks. You have to ask questions: What can the hall in the Imperial Baths be used for? How do you make a concert hall out of a baroque riding hall? How to design an educational center as a teaching tool? I describe this in detail for school assignments in a publication called Diagrams 03. In short, we want our students to learn to think creatively about any assignment. In practice, you don't know what you will encounter. Every situation will be different, every investor and constraint...

Staying with your current assignment.

This semester, we're dealing with the design of the New Village. A former medieval settlement with archaeological excavations of the foundations of dozens of houses, a watermill and a fortress. The location in the south of the Highlands is inspired by the extinct medieval village of Mstěnice.The assignment was brought by Jaroslav Hulín, who knows the area well. The place is very strong and I liked the idea that it would come back to life and become a town or a village, or New Village. As I mentioned, we use the brief to create something like a simulator for creative thinking. From this perspective, it is not so important what the students are working on. However, it is of course advantageous if the topic is also inspirational.

What role do you think context plays, for example the public interest as an important point of view in a democratic society?

I think that respect for the public interest is an obvious part of an architect's responsibility. Designs are created in a certain time and atmosphere, and all this is then automatically manifested in the design. The degree of reflection, the ethical aspect, the social aspect and the relevance is then up to the choice of the author of a particular design and reflects his personal integrity. Our guidance of the work consists, among other things, in helping to define the core values and also in providing feedback.

And if we stay in the New Village?

It is about rehabilitating abandoned places and bringing them to life. We have decided to keep the excavated objects located in the centre of the space - out of piety they are untouched. The New Village with all the buildings is built on an oval ring around it. This ring was part of the brief. It is a kind of spatial regulation. And we are trying to teach creative thinking based on this not-so-common situation.

At the FA, you also conduct doctoral theses, Nikoleta Slováková, one of your PhD students, incidentally became part of your design team for the successful concert hall... What topic did she choose for her PhD thesis?

A city on rails. It was originally the poetic title of her master's thesis, which dealt with the possibilities of developing the Negrelli Viaduct. On the scale of Prague, it would create a new neighbourhood in direct contact with the viaduct. Something like the Loop Line in Osaka, which I partially mapped during my study stay in Japan. The Loop Line is a circular railway that is located on the viaduct around the city centre. After about one kilometer, a resident will always find a stop, or transfer hub. Built into this viaduct is a whole other city with infrastructure, housing and services. So the theme of Nikoleta's work and research was to look for methods to exploit the potential of railways not just as transport structures, but as a compact linear city with everything.

As a professor, you are currently working on your own PhD thesis.

I want to work systematically on evaluating the realisations and concepts in acoustics that I have been working on for almost thirty years - also on a theoretical level. I hope to complete the thesis early next year. It will be entitled Concert Halls as a Musical Instrument.

From your instruments, one could build a small orchestra...

I'll disclose on myself that, paradoxically, I don't have a musical ear, and I don't even know music properly. I don't even know how to play a musical instrument, although I used to experiment and build art objects and try to play them... Until it ended with the DOX+ hall, where Martin Janíček and Filip Jakš played my composition on the construction of a building through ropes in front of the audience. I was inspired by Jan Tabor when he set Zaha Hadid's sketches to music. (Jan Tabor is an Austrian architectural theorist, a publicist of Czech origin, a teacher in Zaha Hadid's studio at the Angewandte in Vienna - ed.).

Music has a certain phrasing, speed, direction... In short, if you create rules on how to play, anything can become notation.

Thank you for the interview.

Jiří Horský