Architecture in dialogue with urbanism. Šimon Vojtík discusses the new faculty studio and the colony at Baba

6/12/2023

At the Faculty of Architecture of the CTU, you lead a new studio dealing with urban detail. What can we imagine under this term?

I still perceive that architecture and urban planning are not very well connected here. In the studio I try to make students think about the architectural assignment in terms of urbanism and vice versa. For me, the urban detail is then the environment we walk through and the effect it has on us. By detail I don't just mean paving, railings and other furnishings. I am interested in the effect of the space, how it is proportioned, its drama, composition and hierarchy. When a student thinks about a territory to enter with his design, he should be aware of all these things.

Urban design and planning is more difficult to discuss with the public than the design of a new house. The topics are often very abstract. How can the transformation of large areas be better communicated to the people?

Urbanism is difficult to share even with the professional public because it is always an abstraction, a symbolic expression of an idea. What you see is not the final shape that would be the first signal. Your intellect has to build the future world itself. Human perception always works on two levels. At first, you like the image. This works for architecture and urbanism, if it is well graphicised it will catch your eye. It certainly plays a big role. But with house design, the visuals are much more connected to reality.

Urban visualizations have one big disadvantage. They anticipate how the urban concept, zoning or regulatory plan will be implemented in concrete terms. However, it is only one of many possibilities and it usually turns out very differently. The visualizations lie a bit and try to present you with the solution that the urban planner likes best. It depends on the degree of abstraction of the perspectives. The more concrete they are, the more they lie, and the more abstract they are, the more difficult it is to imagine the future outcome.

Your students are designing a new neighbourhood in Dolní Počernice. A development will be built on the site, for which your studio Archum has prepared an urban planning study. Why are you returning to a place where you have already worked on a real assignment?

We are trying to create an unusual typology for Prague, urban rental housing on a relatively small scale. It will not be large apartment buildings in standard building blocks, but a much more diverse environment of smaller developments with shared spaces. Our office was constrained by regulation and the existing zoning plan, which is not ideally prepared for this area, but would take a disproportionately long time to change.

At the level of a school assignment, we can design much more freely. For me, the assignment is an opportunity for a mutual dialogue about what a modern, sustainable rental housing city should look like. We don't have to look to the masterplan, but we should address the natural needs of a place, such as a school. We are interested in its involvement in the life of the city, to be a co-creator of a vibrant centre. This is rarely addressed and schools become enclosed complexes. I also asked my colleagues from the SOA studio, who have several successful projects under their belt, including the implementation of the school in Psáry after winning an architectural competition. At this scale, the urban detail is the entire centre of the district with urban amenities, but also the parterre, the green space, the bus stop and their interconnections.

Another assignment is Blatná, where you have been the city architect for many years.

Our office, Archum architekti, was established on the basis of winning the competition for the Blatná master plan. After we submitted it, the mayor at the time approached me if I would like to continue as a city architect. It's an advantageous synergy, because spatial planning is a living organism, a never-ending work, you are always thinking how to improve the spatial plan and move it forward.

The school assignment came out of some frustration. Blatná has a huge potential, but it is unlikely to be fulfilled. It is not like in Prague, where dysfunctional parts are demolished and better neighbourhoods are built because it pays off for investors in the long run. The most interesting for me is the sub-castle, where historic buildings and inappropriate urban structures from the 1990s meet.

You also participated in the design of the reconstruction of Seifert Street in Prague's Žižkov district. Such projects are covered by journalists, they become a political issue and a lot of people are interested in them. But working on small municipalities is perhaps much more difficult.

You're right that some assignments make you happier. You are part of the dialogue, the energy you put in comes back. The hardest part is finding the level where you have to try harder to invest emotionally, professionally, time and financially in the project. I've often been involved in master plans and zoning changes where the response is not like that. I call it cadastral urbanism. You do the bare minimum that property relations will allow. Even so, we are pleased when we come up with a land use concept that is rational and creates a walkable neighborhood with logical public spaces.

You've also tackled the redesign of the Baba residential area, which we all look at from the faculty, especially when no inspiration comes.

We have been preparing a concept for the gradual renewal of the surfaces of public spaces. Baba is also of interest abroad, it is part of the European Heritage Label, but over the decades the streets and the surroundings of the villas have been relatively degraded.

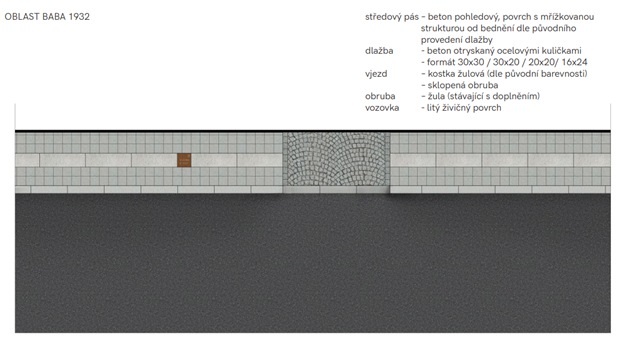

Were you able to discover the original surfaces? When completed, the neighbourhood had rather strange pavements, with a distinctive narrow strip of concrete in the middle. Why did the developers of the colony choose this unusual solution?

We think it was a desire to make public space in a novel, contemporary - functionalist - way. Why have wide cobblestone sidewalks when one lane is enough for pedestrians. There was probably just a mixture of sand and dirt around the concrete strip. At the same time they saved money and used contemporary technology. They also used large cast-in-place concrete blocks with grooves in a number of gardens. We know from surviving documents that savings were made on public lighting, for example. We assume that the pavements were the result of compromises, but designed to still be interesting and modern. But they disappeared relatively quickly under the asphalt. That's why we found the surviving fragments. But we're not creating an exact replica. The requirements are much more demanding today, you have to think about the visually impaired. But we've kept the character and interpreted the design with contemporary materials.

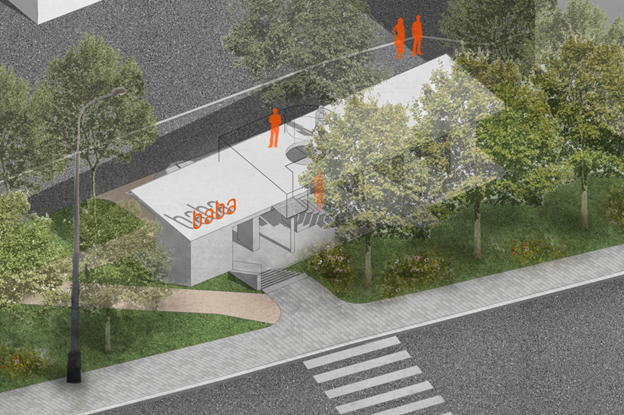

Baba is both a residential area and a tourist attraction, where visitors come to see as well as to visit the gallery. How to connect these two worlds?

That was the essential part of the job. We were looking for places to place information elements so that visitors would not disturb local residents and create an unnecessary burden. An information centre with facilities could be built outside the villa colony itself.

Here the visitor will learn most of the information and then go through the educational circuit. The routes do not only focus on the three most valuable streets, but also include a walking circuit along the edge of Baba with a view of Prague. We have also included an orchard on the hillside below the colony. With more options, visitors will not be concentrated in a narrow corridor.

While browsing the internet, I found out that you are also a music celebrity.

I would object to both of those words. But we have a band called Ba.fnu and we play balfolk. The genre originated in the '60s in France as a desire for people to get together through music and dance. Before that, cultures in Europe influenced each other and a lot of folk dances were created. The Balfolk movement started to dust them off, people coming together and dancing together. We don't have many bands here, we got into balfolk through a friend who studied in France. Balfolk is also popular in Belgium or Poland, and communities are organising festivals across Europe. We play in a way that's fun for us. So we combine folk inspiration with electronic music, for example.

The interview was led by Pavel Fuchs.